ThinkProgress.com, by Natasha Geiling

Oct 28th, 2015

When Alan Barton first arrived at Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery in 2007, he wasn’t expecting to stay very long. The hatchery — the second-largest in the United States — was in trouble, suffering from historically high mortality rates for their microscopic oyster larvae. But Barton knew that in the oyster industry, trouble is just another part of the job.

As manager of the oyster breeding program at Oregon State University, he had already helped one oyster larvae breeding operation navigate through some tough years in 2005, when a bacterial infection appeared to be causing problems for their seeds. To combat the issue, he had created a treatment system that could remove vibrio tubiashii, an infamous killer in the oyster industry, from the water.

Barton made the winding two-hour drive up the Oregon coast from Newport to Netarts, thinking his machines could easily solve whatever was plaguing Whiskey Creek. But when Barton’s $180,000 machine turned on, nothing changed. The hatchery was still suffering massive larvae mortality — months where nearly every one of the billions of tiny larvae housed in the hatchery’s vast network died before it could reach maturity.

Two-hundred miles up the coast in Shelton, Washington, Bill Dewey was also stumped. As director of public affairs for Taylor Shellfish, the country’s largest producer of farmed shellfish, he couldn’t figure out what was causing the hatchery’s tiny larvae to die in huge numbers. He knew aboutvibrio tubiashii, so when the die-offs began, Dewey called Barton and asked if they could install his machines at Taylor Shellfish’s own hatchery in the Puget Sound. And like at Whiskey Creek, the machines did little to stop the mysterious waves of death that were consuming the hatchery’s oyster larvae.

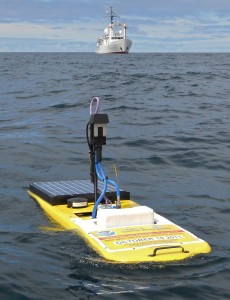

Back in Oregon, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)-vessel rocked by persistent summer winds was approaching Newport. Dick Feely, a senior scientist with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, was just halfway through the first-ever survey meant to measure the amount of carbon dioxide in the surface waters of the Pacific Coast. Already, he could tell from the few samples they had collected that he and his team had the material for a major scientific paper. He called his boss at NOAA to tell him that there was something wrong with the water. It seemed that an increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, propelled by the burning of fossil fuels, was also increasing the acidity of the water.

Read more here