Julia A. Sanders died on December 8, 2021 from complications following spleen-removal surgery at University of Washington Medical Center. She was 41.

Known for her exceptional kindness, loyalty, and intellect, Julia is remembered as a steadfast ally and friend, a loving daughter and sister, and a wise, deeply committed advocate for fishing communities facing increasing impacts of climate change.

Julia served as Deputy Director of the National Fisheries Conservation Center (NFCC) and its Global Ocean Health program. In that role she wore many hats: editor of the Ocean Acidification Report and other publications; manager of social media operations; organizer of fundraising events; administrative manager; researcher; public speaker; and advisor to the Working Group on Seafood and Energy, a trade organization representing seafood-dependent communities and businesses.

A gifted writer of epistolary emails, Julia cultivated friends and supporters on behalf of Global Ocean Health, earning a deeply loyal following of her own. “What a fun gal! Feisty courageous spunky daring forgiving smart caring- and so much more- we are going to miss her like crazy,” recalls Anne Kroeker of Seattle, who with her husband Richard Leeds became close friends with Julia. On learning of Julia’s death, Richard wrote: “Tears and tearing of my heart. My utmost sympathy goes out to you and her family at this devastating loss. Sadly losing Julia is the worst loss of these difficult times. Julia was a great person and greatly appreciated. Marine ecosystems and sustainability lost a great benefactor.”

Alyson Myers, a Virginia shellfish grower and nonprofit leader researching potential for sustainable harvest of sargassum overgrowth in the Atlantic, wrote: “Julia was a joy. She was gifted and intelligent, joyful in her work writing about ways to assist our biggest ecosystem, the ocean. She loved researching solutions and those who pursued them.”

“Julia was completely integral to the work of Global Ocean Health, and was loved by many of the people we work with,” said Brad Warren, President of NFCC. “Personally, I feel like I’ve lost an adopted daughter. Julia first came to work with me 20 years ago at Pacific Fishing Magazine, when we hired her to work in the circulation department. She immediately cracked problems in the magazine’s subscription database that had stumped everyone else.” Warren notes that Julia was soon managing circulation, then took over advertising, where she showed a knack for building new relationships and built her skills in sales and marketing. After leaving the magazine, Warren brought her on board for many projects in publishing, research, editing and administration, leading to her role at NFCC.

At NFCC’s Global Ocean Health Program, Julia earned widespread respect among tribes and fishing communities, scientists and sustainability experts as a skilled analyst and advocate. She played a key role in the organization’s work convening experts and practitioners to navigate impacts of ocean acidification, rising temperatures and sea levels, and related challenges. She built and led NFCC’s work with shellfish growers and coastal engineers to increase coastal resilience in shellfish farms. She edited most of NFCC’s publications and proposals. Julia also led real-time modeling of climate policy (using LCPI’s GHG Explorer software) for NFCC’s work with Washington tribes in 2018, which laid the groundwork for passage of the state’s landmark Climate Commitment Act of 2021, widely considered the strongest climate policy in the United States.

Memorial plans will be announced within a few weeks.

To honor Julia’s determination to protect oceans and fisheries, contributions in her memory may be sent to Global Ocean Health, NFCC, PO Box 30615, Seattle WA 98103.

Tag Archives: climate change

Survivor Salmon that Withstand Drought and Ocean Warming Provide a Lifeline for California Chinook

October 28, 2021, fisheries.noaa.gov

NOAA Fisheries recovery goals include reintroduction to save the late-migrating fish.

A late-migrating spring run Chinook salmon from one of the few Northern California creeks that remain without dams. Credit: Jeremy Notch/UC Santa Cruz.

In drought years and when marine heat waves warm the Pacific Ocean, late-migrating juvenile spring-run Chinook salmon of California’s Central Valley are the ultimate survivors. They are among the few salmon that return to spawning rivers in those difficult years to keep their populations alive. This is according to results published today in Nature Climate Change.

The trouble is that this late-migrating behavior hangs on only in a few rivers where water temperatures remain cool enough for the fish to survive the summer. Today, this habitat is primarily found above barrier dams. Those fish that spend a year in their home streams as juveniles leave in the fall. They arrive in the ocean larger and more likely to survive their 1–3 years at sea.

Scientists examined the ear bones of salmon, called otoliths. These bones incorporate the distinctive isotope ratios of different Central Valley Rivers and the ocean as they grow sequential layers. They looked at Chinook salmon from two tributaries of the Sacramento River without dams that begin beneath Lassen Peak, north of Sacramento. Late-migrating juveniles from Mill Creek and Deer Creek returned from the ocean at much higher rates than more abundant juveniles that leave for the ocean earlier in the spring.

Scientists examined otoliths, the ear bones of salmon, to understand the migration timing of fish that survived drought and poor ocean conditions. Credit: George Whitman and Kimberly Evans/UC Davis

The different timing characteristics of the fish are referred to as “life-history strategies.” Those with a late-migrating life history strategy represented only about 10 percent of outgoing juveniles sampled in fish monitoring traps. However, they were about 60 percent of the returning adult fish across all years, and more than 96 percent of adults from two of the driest years.

“Some years the late migrants were the only life-history strategy that was successful,” said Flora Cordoleani, lead author of the research and associate project scientist with NOAA Fisheries and UC Santa Cruz. “Those fish can make it through the difficult drought conditions on the landscape because they come from the few remaining rivers with accessible high-elevation habitats where water is cool enough through the summer.”

Recovery Strategies Include Reintroduction

The finding underscores the importance of providing secure cool-water habitat for fish so they can survive difficult conditions during drought and ocean warming, said Rachel Johnson, a NOAA Fisheries research scientist, UC Davis researcher and senior author of the study. “Most salmon blocked from their historical habitats appear to migrate just too early and perish once they encounter the warmer water temperatures during droughts.”

“It appears the late-migrating life history has evolved as an insurance policy against the unfavorable spring river conditions that occur during droughts,” said Corey Phillis, a researcher at the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and co-author on the study.

The study also projected how Central Valley river temperatures would rise with climate change, leaving only a few higher-elevation rivers cool enough to still sustain salmon. Many of those areas are above existing dams without fish passage.

NOAA Fisheries has outlined reintroduction of salmon to cold-water rivers above dams as a critical recovery strategy for endangered Sacramento River winter-run Chinook, a NOAA Fisheries Species in the Spotlight. The reintroduction of threatened spring-run Chinook salmon to the San Joaquin River watershed has taken hold. Offspring of reintroduced spring-run Chinook salmon are now returning from the ocean. NOAA Fisheries is also advancing the reintroduction of spring-run Chinook to the upper Yuba River upstream of Englebright Dam.

The study found that temperatures would remain cool enough for salmon to survive in the north Yuba River as the climate changes.

“We need to reconnect salmon to their historical habitats so they can draw from their own climate-adapted bag of tricks to persist in a warming world,” Johnson said.

By growing for a year in their home river, the later-migrating fish head for the ocean bigger than the others and in cooler temperatures. That way, more survive and return to rivers to spawn when marine heatwaves warm the ocean and depress salmon survival. A Marine Heatwave Tracker developed by the Southwest Fisheries Science Center shows that heatwaves have become an increasing presence in the Pacific Ocean in the last decade.

A returning adult spring run Chinook salmon leaps from the water in California’s Central Valley. Credit: Carson Jeffres/UC Davis

Heatwaves Reduce Survival

A large heatwave currently stretching across the Pacific off Northern California and Oregon, as shown by the tracker, may affect salmon survival. Warmer ocean waters are generally less productive, reducing salmon survival and depressing returns to rivers.

NOAA Fisheries’ Northwest Fisheries Science Center has developed a “stoplight chart” that projects survival of different salmon species based on different factors at play in the ocean.

The researchers highlighted the importance of protecting varied life histories that may help their species survive climate change. This is particularly true in California, which is at the southern end of the range of many salmon and at the edge of conditions where they can survive.

“The rarest behaviors observed today may be the most important in our future climate,” said Anna Sturrock of the University of Essex and a co-author of the research.

“We show for the first time that the late-migrating strategy is the life-support for these populations during the current period of extreme warming,” the scientists concluded. “As environmental conditions continue to shift rapidly with climate change, maximizing habitat options across the landscape to enhance adaptive capacity and support climate-resilient behaviours may be crucial to prevent extinction.”

Researchers included:

- NOAA Fisheries’ Southwest Fisheries Science Center

- UC Santa Cruz

- UC Davis

- University of Essex

- Metropolitan Water District of Southern California

- Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography

- Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Can Massive Cargo Ships Use Wind to Go Green?

NyTimes.com June 24th, 2021. By Aurora Almendrahl

Cargo vessels belch almost as much carbon into the air each year as the entire continent of South America. Modern sails could have a surprising impact.

In 2011, Gavin Allwright was living in a village outside Fukushima, Japan, with his wife and three children, when a powerful tsunami destroyed the coastline, splintering homes into debris, crashing a 150-foot fishing boat into the roof of his wife’s parents’ house and setting off a power-plant accident that became the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl.

Allwright had a background in sustainable development, especially as it relates to shipping. In his travels in East Africa and Bangladesh, he had watched traditional sails and masts replaced by outboard motors. The move locked people into a cycle of working to buy fuel, damaging their lives and the environment. In Japan, Allwright had been living a quiet life, running a sustainable farm and dabbling in consulting. Now, it seemed, environmental disaster had followed him there.

To escape the aftermath, the family moved to Allwright’s hometown on the outskirts of London. But Allwright couldn’t stop thinking about the Fukushima disaster. To him, it was a dramatic display of technology going wrong, further proof that the world we built is unsustainable.

Read more about cargo ship emissions

Nature Can Save Humanity From Climate Doom—but Not On Its Own

Matt Simon, Wired.com 5.25.2021

By restoring ecosystems, conservationists can help the land sequester carbon. But it’s still no substitute for drastically cutting emissions.

THE BIGGEST HINT nature ever gave humanity was when it sequestered fossil fuels underground, locking their carbon away from the atmosphere. Only rarely, like when a massive volcano fires a layer of coal into the sky, does that carbon escape its confines to dramatically warm the planet.

But such catastrophes hint at a powerful weapon for fighting climate change: Let nature do its carbon-sequestering thing. By restoring forests and wetlands, humanity can bolster the natural processes that trap atmospheric carbon in vegetation. As long as it all doesn’t catch on fire (or a volcano doesn’t blow it up), such “nature-based solutions,” as climate scientists call them, can help slow global warming.

Earlier this month, scientists put a number on how much of a reduction in global heating these solutions might buy us. Writing in the journal Nature, they used a previous calculation of how much carbon such campaigns could sequester and married that with global warming scenarios from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Basically, they tallied how much of a temperature change could be staved off by keeping this amount of carbon out of the atmosphere.

They found that with an ambitious yet realistic worldwide campaign, humanity might reduce peak warming by 0.1 degrees Celsius under a scenario that assumes a 1.5-degree rise in global temperatures by the year 2055. In a scenario assuming a 2-degree rise by 2085, the savings would be 0.3 degrees. That might not sound like much, in the grand scheme of things. But because nature-based solutions keep on sequestering carbon as long as those habitats remain healthy, in that 1.5-degree scenario we’d actually shave off 0.4 degrees of warming by the year 2100. And that’s a significant difference.

“What we found—which is crucial—is that after that, it continues acting, and [nature-based solutions] have this really important role in cooling our planet up to the end of the century and beyond,” says ecosystems scientist Cécile Girardin of the University of Oxford, the lead author on the paper describing the work. “We’re absolutely not saying nature-based solutions are the solution for climate change. That’s not what the message here is. It’s just a more realistic view of what they can achieve and how we can achieve it.”

So what do these solutions look like? Generally speaking, they aim to both sequester carbon and produce some additional social or ecological benefit.

Alaska’s warming ocean is putting food and jobs at risk, scientists say

By Jordan Evans, CNN, June 28th 2019

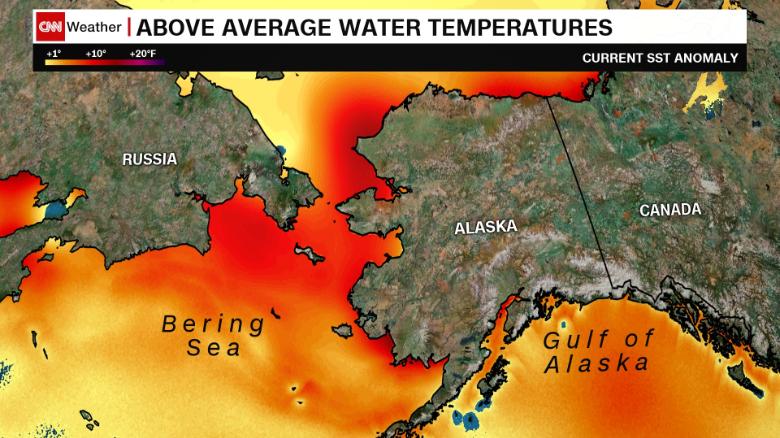

Current sea temperatures around coastal Alaska are pushing 10 degrees above seasonal norms.

The ice around Alaska is not just melting. It’s gotten so low that the situation is endangering some residents’ food and jobs.”The seas are extraordinarily warm. It is impacting the ability for Americans in the region to put food on the table right now,” said University of Alaska climate specialist Rick Thoman.Ocean temperatures in the Chukchi and North Bering seas are nearly 10 degrees Fahrenheit (five degrees Celsius) above normal, satellite data shows.”The northern Bering & southern Chukchi Seas are baking,” Thoman wrote this week in a tweet.

There are immediate local and commercial impacts along the state’s western and northern coastlines, Thoman told CNN. Birds and marine animals are showing up dead, he said, and sea temperatures are warm enough to support algal blooms, which can make the waters toxic to wildlife.

It’s a mounting crisis for many coastal Alaska towns that depend on fishing to support their economy and feed people who live here.”Much of what the people eat there over the course of the year comes from food they harvest themselves,” said climatologist Brian Brettschneider at the International Arctic Research Center. “If people can’t get out on the ice to hunt seals or whales, that affects their food security. It is a human crisis of survivability.”Events like this — when weather patterns align to generate extreme consequences — are also evidence of the growing climate crisis, scientists say.

A perfect storm for warming waters

Ice cover around Alaska normally lasts through the end of May. This year, it disappeared in March, as side-by-side maps showing the same date in March 2013 (left) and 2019 demonstrate, according to the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy.

Atmospheric patterns this year have put Alaska in an unlucky spot, Brettschneider said.The unprecedented warming has been driven by southerly winds in the Bering Sea, with warm air from the south melting the ice at an alarming rate. Ocean temperatures in the region also have never been as warm during the peak of summer, based on seasonal averages. And communities in northern and western Alaska have seen temperatures close to their all-time June records.In short, everything that could have “gone wrong” this year for the ice around Alaska has gone wrong, Brettschneider said.

Read more about the dangerously warming conditions in Alaska

As the oceans acidify, these oyster farmers are fighting back

It’s often hard to notice ecological changes, even when they threaten catastrophe. One oyster company in California hopes to change that.

By Amanda Paulson, Christian Science Monitor, June 25th 2019

When visitors to Hog Island Oyster Co. shuck Pacific oysters at picnic tables overlooking Tomales Bay, it’s the final stage in a story that founding partner Terry Sawyer likes to tell about the shellfish, the bay, and all the steps that went into bringing the briny delicacies to the plate just a few hundred meters from where they were harvested.

It’s a story that now also touches on the carbon cycle, climate change, and the ways in which the very chemistry of the ocean is shifting and how small businesses like Hog Island – along with the entire ocean ecosystem – are struggling to adapt.

The oyster farm helps make abstract issues like ocean acidification and climate change concrete, says Tessa Hill, a marine scientist at the University of California in Davis who studies acidification and has developed a partnership with Mr. Sawyer and Hog Island. “It feels incredibly tangible,” she says. “It’s about the food on our plate; it’s about family businesses; it’s about people’s livelihood along the coast. Ocean acidification and climate change will fundamentally change our relationship with the ocean.”

‘A giant sponge’

Ocean acidification is a direct result of increased carbon dioxide emissions. The oceans – “a giant sponge,” as Professor Hill likes to explain it – absorb about 30% of the carbon dioxide humanity emits. As those levels rise, the chemistry of the ocean fundamentally changes, measurably lowering the pH and making it more acidic. For sea life, one of the biggest risks is to creatures – like shellfish, corals, and sea urchins – that need carbonate ions to build their shells or other structures. The shifting chemistry of the ocean makes those key building blocks scarcer.

Read more about Hog Island’s work with UCSD on ocean acidification

The desperate race to cool the ocean before it’s too late

Technologyreview.com, By Holly Jean Buck, April 23rd

Holly Jean Buck is a fellow at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. This is an adapted excerpt from her upcoming book After Geoengineering: Climate Tragedy, Repair, and Restoration (September 2019, Verso Books).

Coral reefs smell of rotting flesh as they bleach. The riot of colors—yellow, violet, cerulean—fades to ghostly white as the corals’ flesh goes translucent and falls off, leaving their skeletons underneath fuzzy with cobweb-like algae.

Corals live in symbiosis with a type of algae. During the day, the algae photosynthesize and pass food to the coral host. During the night, the coral polyps extend their tentacles and catch passing food. Just 1 °C of ocean warming can break down this coral-algae relationship. The stressed corals expel the algae, and after repeated or prolonged episodes of such bleaching, they can die from heat stress, starve without the algae feeding them, or become more susceptible to disease.

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef—actually a 2,300-kilometer (1,400-mile) system made up of nearly 3,000 separate reefs—has suffered severe bleaching in the past few years. Daniel Harrison, an Australian oceanographer looking at what might be done to buy more time for the Great Barrier Reef, says the situation is getting dire. “There might be as little as 25% of shallow-water coral cover left from pre-anthropogenic times. We don’t really know, because nobody started surveying before 1985,” he tells me. “You’ve got less than 1% of the ocean in coral reefs, and 25% of all marine life. We’re looking at losing all of that really quite quickly, in evolutionary terms. In human-lifetime terms.”

Coral reefs are not just about colorful fish and exotic species. Reefs protect coasts from storms; without them, waves reaching some Pacific islands would be twice as tall. Over 500 million people depend on reef ecosystems for food and livelihoods. Even if the temperature increase eventually stabilizes at 1.5 °C a century or two from now, it’s not known how well coral reef ecosystems will survive a temporary overshoot to higher temperatures.

The corals are like the canary in the coal mine.

The corals are like the canary in the coal mine, Harrison says: “They’re very temperature-sensitive. I really do think it’s just a harbinger of things to come. You know, the coral ecosystem might collapse first, but I think there might be quite a few more ecosystems that’ll follow it. Life is very resilient, but ecosystems as we know them aren’t.”

Read more about corals, cooling the ocean, and climate change

Ocean Heat Waves Are Threatening Marine Life

New York Times, March 4th 2019 –

By Kendra Pierre-Louis and Nadja Popovich

When deadly heat waves hit on land, we hear about them. But the oceans can have heat waves, too. They are now happening far more frequently than they did last century and are harming marine life, according to a new study.

The average number of marine heat wave days for the period 1987-2016, compared to the average for 1925-1954. Orange-red range indicates 18-36+ more marine heat wave days compared to the mid-20th century.

Source: Nature Climate Change | By The New York Times

The study, published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, looked at the impact of marine heat waves on the diversity of life in the ocean. From coral reefs to kelp forests to sea grass beds, researchers found that these heat waves were destroying the framework of many ocean ecosystems.

Marine heat waves are said to occur when sea temperatures are much warmer than normal for at least five consecutive days.

Scientists estimate that the oceans have absorbed more than 90 percent of the heat trapped by excess greenhouse gases since midcentury. Humans have added these gases to the atmosphere largely by burning fossil fuels, like coal and natural gas, for energy.

An estimated one billion people depend on coral reefs, which are highly sensitive to temperature, for food or income. Credit Gabriel Barathieu/Biosphoto/Minden Pictures

Bleached coral in Kaneohe Bay off Oahu, Hawaii. Credit Caleb Jones/AP

An earlier study by some of the same researchers found that, from 1925 to 2016, marine heat waves became, on average, 34 percent more frequent and 17 percent longer. Over all, there were 54 percent more days per year with marine heat waves globally.

The most severe years tended to be El Niño years. Warmer ocean temperatures are one of the characteristics of an El Niño pattern.

“There’s also some indication that El Niños have been getting more extreme with climate change,” said Eric C. J. Oliver, an assistant professor of physical oceanography at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who was a co-author of the study. But regional marine heat waves can happen even without an El Niño, he said.

Business, taxpayers save money with Initiative 1631. Vote yes.

This commentary originally appeared in the Puget Sound Business Journal

By Jeff Stonehill

Over decades running Alaska fishing and Seattle construction businesses, my crew and I burned a lot of fuel. Ironically, our livelihood came from fish stocks and forests that now are choking on the fumes from burning fuel. The costs of carbon emissions were hidden in the past, but they’re coming home to roost.

Over decades running Alaska fishing and Seattle construction businesses, my crew and I burned a lot of fuel. Ironically, our livelihood came from fish stocks and forests that now are choking on the fumes from burning fuel. The costs of carbon emissions were hidden in the past, but they’re coming home to roost.

Pollution has become a fast-expanding hole in our wallets. As taxpayers, we pay billions to fight wildfires, floods, droughts, and a roster of other troubles that are either caused or amplified by carbon emissions from all that fuel we burn.

We can mend this hole by passing Initiative 1631 on November 6. This initiative applies a proven recipe for cutting pollution, reducing fuel consumption, and goosing economic growth. It’s called “price-and-invest” emissions policy: Put a modest price on carbon pollution, then invest the money to help people boost fuel efficiency, clean energy, and resilience against the consequences of pollution.

Don’t want your tax dollars wasted? Me neither. Wildfires are burning our money today—aggravated by climate-amplified heat and drought, along with poor fuel-management practices. Over the last five years, fighting the new wave of “megafires” cost Washington $1 billion, according to the Department of Natural Resources.

Climate-intensified floods, hurricanes and rising seas aren’t free either. Our US tax dollars are bailing out a federal flood insurance system that was swimming in $30 billion of red ink by 2017.

That doesn’t even count the cost of degrading the natural resources that gave my family a good living. Cutting pollution will help control the growing damage to our fisheries, our forests, and our snow-fed water supplies. Seafood alone supports nearly 61,000 jobs in Washington. Wood products support 101,000 jobs. Nearly 200,000 depend on outdoor recreation.

Climate impacts and ocean acidification are undermining these jobs today. Puget Sound’s unraveling foodweb is forcing drastic measures to protect dwindling Chinook salmon and endangered resident orca whales that feed on them. Chinook salmon are dying within weeks after entering saltwater. Massive blooms of toxic algae are thriving in warm, carbon-acidified seawater, displacing healthy prey species that sustain our fish stocks. These toxic algae are undermining coastal tourism and fishing businesses by forcing health authorities to shut down razor clam and Dungeness crab harvests.

Tired of paying the tab for unnecessary pollution? Me too. Thankfully, we can prosper by cutting the emissions behind these problems. Other states are already doing it successfully.

Despite the fear-mongering claims in oil-funded TV ads, other states have demonstrated that cutting carbon pollution with policies like Initiative 1631 saves money and strengthens the economy.

On the East Coast, businesses and consumers saved $1 billion through efficiency and clean power funded by revenue from a carbon price over the last three years. Nine states from Maine to Maryland share a regional price-and-invest policy to reduce carbon emissions from power plants. Instead of buying ever more imported fossil fuels, they kept $1 billion in their wallets.

Those same states reduced regulated emissions by more than 50% over the last nine years. Their efficiency and clean energy projects generated tens of thousands of new jobs, and added billions of dollars to their economy. They did it by investing carbon revenues to build a cleaner economy.

A key ingredient here is common sense. If we raise revenues to solve a problem, that’s what we should use those revenues for. That’s what Initiative 1631 does.

Accountability matters. This measure proposes a carbon fee, not a tax. That legal distinction keeps stray hands out of the till: Fee revenue can only be used for the purposes it is raised for. No unrelated pet projects allowed.

Under 1631, investments of carbon revenue will be dedicated to reduce GHG emissions (70%), to build climate resilience in waters and lands at the front lines of climate impacts (25%), and to help communities cope with impacts of climate change like wildfire, flooding, and the need to educate kids so they can deal with the problem (5%). About one twentieth of the money for pollution reduction is reserved to help fossil fuel employees transition to other work as demand for fossil fuels drops.

This initiative is not a retread of the “carbon tax” measure that voters rejected in 2016. That year, some climate advocates promoted a wasteful and ineffective measure to tax carbon emissions and then give away the money in business tax breaks and “rebates” for low-income people. That might feel good, but it doesn’t do much to reduce pollution, and it doesn’t deliver the savings or the jobs we can get from this year’s stronger, smarter policy.

Come November 6, we have a chance to put our money to work where it delivers. Vote for Initiative 1631.

BIO: Jeff Stonehill ran a commercial salmon fishing business in Alaska for 20 years, and a construction business in Seattle for 15. He participates in the Working Group on Seafood and Energy, which supplied information for this article.

Note: Global Ocean Health and the Working Group on Seafood and Energy provided assistance with this piece

Brad Warren speaks about climate change, seafood, and initiative 1631

National Fisheries Conservation Center and its Global Ocean Health program’s Executive Director Brad Warren speaks on Seattle’s Morning News with Dave Ross about ensuring initiative 1631 provides a fair solution for working lands and working waters, as well as rural communities. He tackles some of the most common opposing viewpoints and shares why price-and-invest policies like 1631 are the ones that work best. Interview starts at 12:47. Or, to listen directly from the start of his interview, click here.