October 28, 2021, fisheries.noaa.gov

NOAA Fisheries recovery goals include reintroduction to save the late-migrating fish.

A late-migrating spring run Chinook salmon from one of the few Northern California creeks that remain without dams. Credit: Jeremy Notch/UC Santa Cruz.

In drought years and when marine heat waves warm the Pacific Ocean, late-migrating juvenile spring-run Chinook salmon of California’s Central Valley are the ultimate survivors. They are among the few salmon that return to spawning rivers in those difficult years to keep their populations alive. This is according to results published today in Nature Climate Change.

The trouble is that this late-migrating behavior hangs on only in a few rivers where water temperatures remain cool enough for the fish to survive the summer. Today, this habitat is primarily found above barrier dams. Those fish that spend a year in their home streams as juveniles leave in the fall. They arrive in the ocean larger and more likely to survive their 1–3 years at sea.

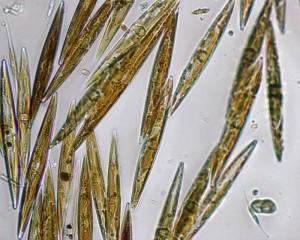

Scientists examined the ear bones of salmon, called otoliths. These bones incorporate the distinctive isotope ratios of different Central Valley Rivers and the ocean as they grow sequential layers. They looked at Chinook salmon from two tributaries of the Sacramento River without dams that begin beneath Lassen Peak, north of Sacramento. Late-migrating juveniles from Mill Creek and Deer Creek returned from the ocean at much higher rates than more abundant juveniles that leave for the ocean earlier in the spring.

Scientists examined otoliths, the ear bones of salmon, to understand the migration timing of fish that survived drought and poor ocean conditions. Credit: George Whitman and Kimberly Evans/UC Davis

The different timing characteristics of the fish are referred to as “life-history strategies.” Those with a late-migrating life history strategy represented only about 10 percent of outgoing juveniles sampled in fish monitoring traps. However, they were about 60 percent of the returning adult fish across all years, and more than 96 percent of adults from two of the driest years.

“Some years the late migrants were the only life-history strategy that was successful,” said Flora Cordoleani, lead author of the research and associate project scientist with NOAA Fisheries and UC Santa Cruz. “Those fish can make it through the difficult drought conditions on the landscape because they come from the few remaining rivers with accessible high-elevation habitats where water is cool enough through the summer.”

Recovery Strategies Include Reintroduction

The finding underscores the importance of providing secure cool-water habitat for fish so they can survive difficult conditions during drought and ocean warming, said Rachel Johnson, a NOAA Fisheries research scientist, UC Davis researcher and senior author of the study. “Most salmon blocked from their historical habitats appear to migrate just too early and perish once they encounter the warmer water temperatures during droughts.”

“It appears the late-migrating life history has evolved as an insurance policy against the unfavorable spring river conditions that occur during droughts,” said Corey Phillis, a researcher at the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and co-author on the study.

The study also projected how Central Valley river temperatures would rise with climate change, leaving only a few higher-elevation rivers cool enough to still sustain salmon. Many of those areas are above existing dams without fish passage.

NOAA Fisheries has outlined reintroduction of salmon to cold-water rivers above dams as a critical recovery strategy for endangered Sacramento River winter-run Chinook, a NOAA Fisheries Species in the Spotlight. The reintroduction of threatened spring-run Chinook salmon to the San Joaquin River watershed has taken hold. Offspring of reintroduced spring-run Chinook salmon are now returning from the ocean. NOAA Fisheries is also advancing the reintroduction of spring-run Chinook to the upper Yuba River upstream of Englebright Dam.

The study found that temperatures would remain cool enough for salmon to survive in the north Yuba River as the climate changes.

“We need to reconnect salmon to their historical habitats so they can draw from their own climate-adapted bag of tricks to persist in a warming world,” Johnson said.

By growing for a year in their home river, the later-migrating fish head for the ocean bigger than the others and in cooler temperatures. That way, more survive and return to rivers to spawn when marine heatwaves warm the ocean and depress salmon survival. A Marine Heatwave Tracker developed by the Southwest Fisheries Science Center shows that heatwaves have become an increasing presence in the Pacific Ocean in the last decade.

A returning adult spring run Chinook salmon leaps from the water in California’s Central Valley. Credit: Carson Jeffres/UC Davis

Heatwaves Reduce Survival

A large heatwave currently stretching across the Pacific off Northern California and Oregon, as shown by the tracker, may affect salmon survival. Warmer ocean waters are generally less productive, reducing salmon survival and depressing returns to rivers.

NOAA Fisheries’ Northwest Fisheries Science Center has developed a “stoplight chart” that projects survival of different salmon species based on different factors at play in the ocean.

The researchers highlighted the importance of protecting varied life histories that may help their species survive climate change. This is particularly true in California, which is at the southern end of the range of many salmon and at the edge of conditions where they can survive.

“The rarest behaviors observed today may be the most important in our future climate,” said Anna Sturrock of the University of Essex and a co-author of the research.

“We show for the first time that the late-migrating strategy is the life-support for these populations during the current period of extreme warming,” the scientists concluded. “As environmental conditions continue to shift rapidly with climate change, maximizing habitat options across the landscape to enhance adaptive capacity and support climate-resilient behaviours may be crucial to prevent extinction.”

Researchers included:

- NOAA Fisheries’ Southwest Fisheries Science Center

- UC Santa Cruz

- UC Davis

- University of Essex

- Metropolitan Water District of Southern California

- Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography

- Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory