By Jordan Evans, CNN, June 28th 2019

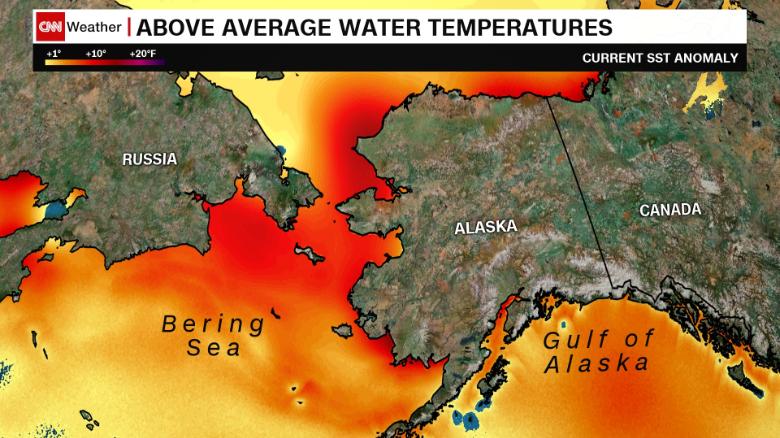

Current sea temperatures around coastal Alaska are pushing 10 degrees above seasonal norms.

The ice around Alaska is not just melting. It’s gotten so low that the situation is endangering some residents’ food and jobs.”The seas are extraordinarily warm. It is impacting the ability for Americans in the region to put food on the table right now,” said University of Alaska climate specialist Rick Thoman.Ocean temperatures in the Chukchi and North Bering seas are nearly 10 degrees Fahrenheit (five degrees Celsius) above normal, satellite data shows.”The northern Bering & southern Chukchi Seas are baking,” Thoman wrote this week in a tweet.

There are immediate local and commercial impacts along the state’s western and northern coastlines, Thoman told CNN. Birds and marine animals are showing up dead, he said, and sea temperatures are warm enough to support algal blooms, which can make the waters toxic to wildlife.

It’s a mounting crisis for many coastal Alaska towns that depend on fishing to support their economy and feed people who live here.”Much of what the people eat there over the course of the year comes from food they harvest themselves,” said climatologist Brian Brettschneider at the International Arctic Research Center. “If people can’t get out on the ice to hunt seals or whales, that affects their food security. It is a human crisis of survivability.”Events like this — when weather patterns align to generate extreme consequences — are also evidence of the growing climate crisis, scientists say.

A perfect storm for warming waters

Ice cover around Alaska normally lasts through the end of May. This year, it disappeared in March, as side-by-side maps showing the same date in March 2013 (left) and 2019 demonstrate, according to the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy.

Atmospheric patterns this year have put Alaska in an unlucky spot, Brettschneider said.The unprecedented warming has been driven by southerly winds in the Bering Sea, with warm air from the south melting the ice at an alarming rate. Ocean temperatures in the region also have never been as warm during the peak of summer, based on seasonal averages. And communities in northern and western Alaska have seen temperatures close to their all-time June records.In short, everything that could have “gone wrong” this year for the ice around Alaska has gone wrong, Brettschneider said.

Read more about the dangerously warming conditions in Alaska