Julia A. Sanders died on December 8, 2021 from complications following spleen-removal surgery at University of Washington Medical Center. She was 41.

Known for her exceptional kindness, loyalty, and intellect, Julia is remembered as a steadfast ally and friend, a loving daughter and sister, and a wise, deeply committed advocate for fishing communities facing increasing impacts of climate change.

Julia served as Deputy Director of the National Fisheries Conservation Center (NFCC) and its Global Ocean Health program. In that role she wore many hats: editor of the Ocean Acidification Report and other publications; manager of social media operations; organizer of fundraising events; administrative manager; researcher; public speaker; and advisor to the Working Group on Seafood and Energy, a trade organization representing seafood-dependent communities and businesses.

A gifted writer of epistolary emails, Julia cultivated friends and supporters on behalf of Global Ocean Health, earning a deeply loyal following of her own. “What a fun gal! Feisty courageous spunky daring forgiving smart caring- and so much more- we are going to miss her like crazy,” recalls Anne Kroeker of Seattle, who with her husband Richard Leeds became close friends with Julia. On learning of Julia’s death, Richard wrote: “Tears and tearing of my heart. My utmost sympathy goes out to you and her family at this devastating loss. Sadly losing Julia is the worst loss of these difficult times. Julia was a great person and greatly appreciated. Marine ecosystems and sustainability lost a great benefactor.”

Alyson Myers, a Virginia shellfish grower and nonprofit leader researching potential for sustainable harvest of sargassum overgrowth in the Atlantic, wrote: “Julia was a joy. She was gifted and intelligent, joyful in her work writing about ways to assist our biggest ecosystem, the ocean. She loved researching solutions and those who pursued them.”

“Julia was completely integral to the work of Global Ocean Health, and was loved by many of the people we work with,” said Brad Warren, President of NFCC. “Personally, I feel like I’ve lost an adopted daughter. Julia first came to work with me 20 years ago at Pacific Fishing Magazine, when we hired her to work in the circulation department. She immediately cracked problems in the magazine’s subscription database that had stumped everyone else.” Warren notes that Julia was soon managing circulation, then took over advertising, where she showed a knack for building new relationships and built her skills in sales and marketing. After leaving the magazine, Warren brought her on board for many projects in publishing, research, editing and administration, leading to her role at NFCC.

At NFCC’s Global Ocean Health Program, Julia earned widespread respect among tribes and fishing communities, scientists and sustainability experts as a skilled analyst and advocate. She played a key role in the organization’s work convening experts and practitioners to navigate impacts of ocean acidification, rising temperatures and sea levels, and related challenges. She built and led NFCC’s work with shellfish growers and coastal engineers to increase coastal resilience in shellfish farms. She edited most of NFCC’s publications and proposals. Julia also led real-time modeling of climate policy (using LCPI’s GHG Explorer software) for NFCC’s work with Washington tribes in 2018, which laid the groundwork for passage of the state’s landmark Climate Commitment Act of 2021, widely considered the strongest climate policy in the United States.

Memorial plans will be announced within a few weeks.

To honor Julia’s determination to protect oceans and fisheries, contributions in her memory may be sent to Global Ocean Health, NFCC, PO Box 30615, Seattle WA 98103.

Tag Archives: shellfish

Fight Pollution, Cut the Oil Boy’s Allowance: Pass I-1631, say Fishermen

Nov 2, 2018

By Brad Warren, Erling Skaar, Jeff Stonehill, Amy Grondin, Jeb Wyman, Pete Knutson, and Larry Soriano

Erling Skaar with the F/V North American

As voters consider a November 6 ballot measure to cut carbon pollution in Washington state, you might not expect fishermen and marine suppliers to defend an initiative that big oil—in a tsunami of misleading ads—claims will drive up fuel bills and achieve nothing.

Nice try, oil boys. Keep huffing. Initiative 1631 is our best shot to protect both our wallets and the waters that feed us all. We’re voting yes.

We depend on fisheries, so we need an ocean that keeps making fish. That requires deep cuts in carbon emissions. And yes, we burn a lot of fuel to harvest seafood and bring it to market—so we need affordable energy. Washington’s Initiative 1631 provides the tools to deliver both.

Carbon emissions are already damaging the seafood industry in Washington and beyond. This pollution heats our rivers and oceans and it acidifies seawater. These changes drive an epidemic of harvest closures, fish and shellfish die-offs, even dissolving plankton. Pollution is unraveling marine foodwebs that sustain both wild capture and aquaculture harvests—jeopardizing dinner for more than 3 billion people worldwide. Today Washington’s endangered resident orca whales are starving for lack of Chinook salmon. To us, that’s a sobering sign: No one catches fish better than an orca.

We are not amateurs or do-gooders. We are Washington residents who have built careers and businesses in fisheries. Several of us come from families that have worked the sea for generations. All of us have benefited from our region’s strict and sustainable harvest management regimes.

Our legacies and our livelihoods are being eroded by the ocean consequences of carbon emissions. Even the best-managed fisheries cannot long withstand this corrosion. Knowing this, we have done our homework. We opposed an ineffective and costly carbon tax proposed two years ago in Washington. We did not lightly endorse Initiative 1631. We pushed hard to improve it first.

We like the result. The initiative charges a fee on carbon pollution, then invests the money to “help people become the solution.” That is a proven recipe for cutting emissions and building a stronger, cleaner economy.

In the Nov. 6 election, Washington citizens have a chance to face down the oil lobby that has stifled progress on carbon emissions for many years. But we cannot watch silently as some of our neighbors fall under the $31 million blitz of fear-mongering ads that oil has unleashed to fight this measure. We know and respect people in the oil industry. But they are not playing straight this time.

Here we refute their misleading claims.

MYTH: Oil pays, but other polluters are unfairly exempted

REALITY: A fee on all heavy industries would kill jobs, exporting pollution instead of cutting it

If you want to cut pollution, it pays to aim. Targeting carbon prices where they work—not where they flop—is necessary to reduce pollution and build a stronger, cleaner economy. That’s what Initiative 1631 does.

If you want to cut pollution, it pays to aim. Targeting carbon prices where they work—not where they flop—is necessary to reduce pollution and build a stronger, cleaner economy. That’s what Initiative 1631 does.

For some key industries, a price on carbon emissions kills jobs without cutting pollution. That’s what happens to aircraft manufacturers, or concrete, steel and aluminum makers. They use lots of energy and face out-of-state competitors (I-1631 Sec. 8). Suppose we slap a carbon fee on them as the oil boys pretend to want. Sure enough, their competition promptly seizes their markets and their jobs, and factories flee the state. Way to go, oil boys! You left pollution untouched, and you crushed thousands of good Washington jobs!

By waiving the fee for vital but vulnerable industries, Initiative 1631 keeps jobs and manufacturing here in Washington. The initiative helps these companies reduce emissions over time, just as it does for the rest of us. In fact, it even reserves funds for retraining and assistance so fossil-fuel workers can transition to new careers. That could become necessary as the state migrates from dirty fuels to a cleaner, more efficient economy (Sec 4,(5)).

In a clean-energy future, Washington will still need local manufacturing and basic materials. Keeping these businesses here allows the rest of us to buy from local producers, instead of paying (and polluting) more to haul those goods back to Washington.

The oil boys also whine about Washington’s last coal plant, in Centralia. It is exempt from the fee because it is scheduled to close by 2025 under a legal agreement. Why shoot a dead man?

MYTH: This is an unfair tax on low-income families.

REALITY: The poor get help to cut fuel and energy bills.

Initiative 1631 provides both the mandate and the means to avoid raising energy costs for lower income people. Carbon revenues fund energy efficiency and more clean power—permanently reducing fuel consumption. The measure reserves 35% of all investments to benefit vulnerable, low-income communities (Sec 3, (5)(a)) —ensuring a fair share for those of modest means. It also funds direct bill assistance where needed to prevent unfair energy burdens on those who can least afford it (Sec 4, (4)(a)).

MYTH: The fee would burden businesses and households

REALITY: I-1631 will cut fuel bills by boosting efficiency, clean energy

Despite the scaremongering from oil companies, consumers and businesses are saving hundreds of millions of dollars in states that have policies like I-1631. How? Carbon revenues fund more clean energy and fuel-saving improvements (such as heat pumps, solar and wind power, and fuel efficiency retrofits). That’s what 1631 will provide in WA. These investments reduce fuel bills. Even the big oil companies use internal carbon pricing, as do hundreds of major corporations. Their internal prices drive energy efficiency and lower emissions in their own operations, cutting their costs; they also help position the firms to thrive in a carbon-constrained world. If this didn’t pay, big oil wouldn’t do it. Big oil producers like Exxon hate spending money on fuel they don’t need to burn. They just don’t want the rest of us to have the same tool.

Nine East Coast states are using carbon revenues to cut both their fuel bills and their emissions. Their Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) helped them avoid spending $1.37 billion on imported fuel in the last 3 years alone. If refineries do pass along Washington’s fee to consumers (as we expect), households and drivers here will still reap the same kind of benefits as ratepayers back East: efficiency and clean energy investments funded by the fee will reduce our energy bills. A heat pump alone can cut home heating costs by half to two thirds. The fee starts in 2020 at less than 5% of today’s gasoline prices, and rises to about 13% by 2030. Fuel efficiency investments help protect people who still need fuel-burning trucks and vehicles: you can’t haul timber or fish to market with a bus pass. For those who cannot switch to transit, electric vehicles, or low-carbon fuels, the initiative funds fuel efficiency improvements (Sec 4, (1)(d)(iii)). The resulting fuel savings can easily outpace the cost of the fee. One example: HyTech Power, in Redmond, sells a system that increases combustion efficiency in large diesel engines, saving at least 20%. This retrofit alone (one of many proven options) could save diesel users more than the future cost of the carbon fee projected by its opponents.

MYTH: I-1631 is an unproven policy.

REALITY: Price-and-invest policies are clobbering pollution in other states.

Pete Knutson with the F/V Loki

Carbon price-and-invest policies are delivering strong results worldwide. Here in the US, a price-and-invest policy helped California cut emissions enough to surpass its 2020 goals back in 2016—four years early. The East Coast states in the RGGI price-and-invest system have reduced their emissions by 50% since 2009, far surpassing their goal. By cutting harmful pollution, the multi-state RGGI program avoided $5.7 billion worth of healthcare costs and associated productivity losses, saving hundreds of lives. From Maryland to Maine, the RGGI program generated 14,500 job-years of employment and net economic benefit of $1.4 billion during 2015-2017 alone. This program saved ratepayers more than $220 million (net) on energy bills over the last three years. The nine RGGI states achieve this by committing 70% of their carbon revenues—about the same as I-1631—to increase efficiency and clean energy. That’s a recipe for success.

MYTH: 1631 lacks oversight, will waste money.

REALITY: Accountability and oversight are robust.

Accountability is built into this initiative from the ground up, starting with the revenue mechanism: It is a fee not a tax, so the money can’t be diverted. By law, fee revenues must be spent addressing the problem the fee is meant to tackle—in this case reducing carbon pollution and its many costly consequences in Washington. That means no pet projects, and no sweeping money into the general fund.

All investments must earn approval from a 15-member public board that includes experts in relevant technology and science, along with business, health, and community and tribal leaders (Sec. 11). The legislature and board will periodically audit the process to ensure effectiveness (sec. 12).

The oversight panel is deliberately designed to hold state agencies accountable. Washington treaty Indian tribes—who both distrust and respect the agencies— insisted that public members must hold more votes than bureaucrats, who get only four voting seats (Sec. 11 (5)). That power balance restrains the agencies’ ability to grab funds, yet it ensures the panel can tap their genuine expertise. To lead the oversight board, a strong chairman has an independent staff within the governor’s office. This provides the spine and staff power needed to ride herd on agencies and lead a crosscutting mission to combat climate change—a task that spans authorities and talents found throughout the state government.

A word about wasting money: If the oil boys honestly believed 1631 would waste our money, they wouldn’t fear it. They condemn the fee, but we know the price doesn’t worry them, since they use carbon prices themselves. They have poured more than $31 million into fighting 1631—the most expensive initiative campaign in Washington history—for one simple reason: The money will help the rest of us buy less fuel. Pity the oil boys. By passing this initiative, voters can cut their allowance.

Let’s do it.

Note: The authors are Puget Sound-based fishermen, marine suppliers, and policy leaders.

‘One morning we came in and everything was dead’: Climate change and Oregon oysters

As the state’s only shellfish hatchery, it’s a large part of the oyster industry in the region.

Alan Barton is the Production Manager at Whiskey Creek.

He’s worked there for the past decade and says they play a big part bringing shellfish from ocean to plate.

“We probably produce about a third of all oyster larvae on the West Coast,” says Barton.

In 2007 and 2008, the whole operation was nearly shut down.

Something changed in the waters of Netarts Bay, which Whiskey Creek uses to spawn oysters.

Their output was reduced by nearly 75 percent each year.

A hatchery out of business would have had a substantial impact on the oyster industry.

The Washington Shellfish Initiative estimated that shellfish growers employ, directly and indirectly, more than 3,200 people across the Pacific Northwest with an economic impact around $270 million.

“In these rural areas along the coastline, 3,000 jobs are pretty important,” says Barton. “These are just blue collar guys.”

Initially, Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery staff believed their mass die-offs were caused by biological problems, like foreign bacteria – or the wrong type of algae used for food.

“I remember one morning, we came in and everything was dead, all of it,” says Barton.

“It was our worst day, but also our best day. Because it’s when we realized the problem might be with the water from the bay.”

That is when the hatchery turned to Oregon State University for help.

The Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery believed “ocean acidification,” a byproduct of climate change, was to blame.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) define ocean acidification, or “OA” for short as, “a reduction in the pH of the ocean over an extended period of time, caused primarily by uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere.”

In essence, more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere the more it will sink into the ocean.

Once enough of it gets into the water, it’s chemical makeup changes.

That can have a wide variety of effects on local animals and the ecosystem they live in.

George Waldbusser, Associate Professor at OSU, says ocean acidification is undoubtedly connected to climate change.

“By burning fossil fuels, we’ve increased the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere by 30 percent,” he says. “That’s lowered the pH of the ocean — or the acidity of the ocean — by about 30 percent, which shifts the saturation state and makes it harder for organisms to make shells.”

The drop in acid in water is troubling for shellfish.

During the first two weeks of an oyster’s life they are especially sensitive to the level of oxygen and acid in the water.

In high acid events, oyster’s shells deform – and often times they die.

Waldbusser believes conditions will only get harder, not easier on shellfish.

“We know the chemistry will change and these extreme events will get worse and worse. And so periods of time that are easy or good to grow oysters will diminish in time for the hatchery,” he says.

Fortunately, OSU was able to help the Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery.

Burke Hales, a professor at OSU, created a way to measure the chemistry of the water used to spawn shellfish.

That allows the hatchery to treat the water and provide a successful growing environment for their oysters.

“With that knowledge,” Hales says, “the Whiskey Creek folks are able to change their operations: the timing of their water pumping, how they condition the water. Now they’re back to almost 100 percent of their pre-crash productivity.”

But Hales believes the current method of overcoming ocean acidification is not a long-term solution.

“Netarts Bay has always had some good times; it’s always had some bad times. But the frequency of the good times is less and the frequency of the bad times is greater. And the bad times are a little bit worse than they used to be,” says Hales.

To combat the problem for the long term researchers at OSU point to reducing the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere which causes ocean acidification.

“We have to recognize that fossil fuel emissions are a cause of climate change and ocean acidification. We also have to recognize that we’ve relied on them for a long time and we have to find reasonable transition plans to move away from fossil fuels and into alternative energy,” says Waldbusser.

For Barton at the Whiskey Creeks Shellfish Hatchery, he’s thankful they’ve found a way to overcome the effect the effect carbon dioxide has had on the ocean.

“If we had not figured out what ocean acidification was doing to this hatchery we would for sure be out of business,” he says.

However, he is not confident their current techniques for treating the water will sustain them forever.

“The short term prospects are pretty good. But within the next couple of decades we’re going to cross a line I don’t think we’re going to be able to come back from,” he says. “A lot of people have the luxury of being skeptics about climate change and ocean acidification. But we don’t have that choice. If we don’t change the chemistry of the water going into our tanks, we’ll be out of business. It’s that simple for us.”

Originally published here

Our Deadened, Carbon-Soaked Seas

The New York Times, October 15th, 2015,

Ocean and coastal waters around the world are beginning to tell a disturbing story. The seas, like a sponge,

are absorbing increasing amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, so much so that the chemical balance of our oceans and coastal waters is changing and a growing threat to marine ecosystems. Over the past 200 years, the world’s seas have absorbed more than 150 billion metric tons of carbon from human activities. Currently, that’s a worldwide average of 15 pounds per person a week, enough to fill a coal train long enough to encircle the equator 13 times every year.

are absorbing increasing amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, so much so that the chemical balance of our oceans and coastal waters is changing and a growing threat to marine ecosystems. Over the past 200 years, the world’s seas have absorbed more than 150 billion metric tons of carbon from human activities. Currently, that’s a worldwide average of 15 pounds per person a week, enough to fill a coal train long enough to encircle the equator 13 times every year.

We can’t see this massive amount of carbon dioxide that’s going into the ocean, but it dissolves in seawater as carbonic acid, changing the water’s chemistry at a rate faster than seen for millions of years. Known as ocean acidification, this process makes it difficult for shellfish, corals and other marine organisms to grow, reproduce and build their shells and skeletons.

About 10 years ago, ocean acidification nearly collapsed the annual $117 million West Coast shellfish industry, which supports more than 3,000 jobs. Ocean currents pushed acidified water into coastal areas, making it difficult for baby oysters to use their limited energy to build protective shells. In effect, the crop was nearly destroyed.

Human health, too, is a major concern. In the laboratory, many harmful algal species produce more toxins and bloom faster in acidified waters. A similar response in the wild could harm people eating contaminated shellfish and sicken, even kill, fish and marine mammals such as sea lions.

Increasing acidity is hitting our waters along with other stressors. The ocean is warming; in many places the oxygen critical to marine life is decreasing; pollution from plastics and other materials is pervasive; and in general we overexploit the resources of the ocean. Each stressor is a problem, but all of them affecting the oceans at one time is cause for great concern. For both the developing and developed world, the implications for food security, economies at all levels, and vital goods and services are immense.

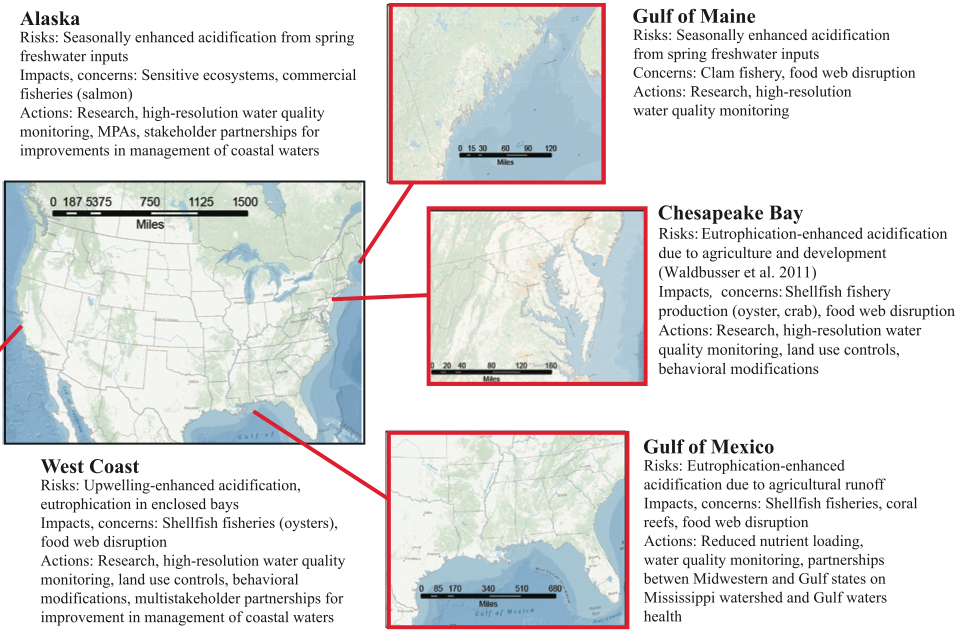

This year, the first nationwide study showing the vulnerability of the $1 billion U.S. shellfish industry to ocean acidification revealed a considerable list of at-risk areas. In addition to the Pacific Northwest, these areas include Long Island Sound, Narragansett Bay, Chesapeake Bay, the Gulf of Mexico, and areas off Maine and Massachusetts. Already at risk are Alaska’s fisheries, which account for nearly 60 percent of the United States commercial fish catch and support more than 100,000 jobs.

Ocean acidification is weakening coral structures in the Caribbean and in cold-water coral reefs found in the deep waters off Scotland and Norway. In the past three decades, the number of living corals covering the Great Barrier Reef has been cut in half, reducing critical habitat for fish and the resilience of the entire reef system. Dramatic change is also apparent in the Arctic, where the frigid waters can hold so much carbon dioxide that nearby shelled creatures can dissolve in the corrosive conditions, affecting food sources for indigenous people, fish, birds and marine mammals. Clear pictures of the magnitude of changes in such remote ocean regions are sparse. To better understand these and other hotspots, more regions must be studied.

Read more here

New England Takes on Ocean Pollution State By State

By Patrick Whittle, Associated Press, March 30, 2015

Portland, Maine — A group of state legislators in New England want to form a multi-state pact to counter increasing ocean acidity along the East Coast, a problem they believe will endanger multi-million dollar fishing industries if left unchecked.

The legislators’ effort faces numerous hurdles: They are in the early stages of fostering cooperation between many layers of government, hope to push for potentially expensive research and mitigation projects, and want to use state laws to tackle a problem scientists say is the product of global environmental trends.

But the legislators believe they can gain a bigger voice at the federal and international levels by banding together, said Mick Devin, a Maine representative who has advocated for ocean research in his home state. The states can also push for research to determine the impact that local factors such as nutrient loading and fertilizer runoff have on ocean acidification and advocate for new controls, he said.

“We don’t have a magic bullet to reverse the effects of ocean acidification and stop the world from pumping out so much carbon dioxide,” Devin said. “But there are things we can do locally.”

The National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration says the growing acidity of worldwide oceans is tied to increased atmospheric carbon dioxide, and they attribute the growth to fossil fuel burning and land use changes. The atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide increased from 280 parts per million to over 394 parts per million over the past 250 years, according to NOAA.

Carbon dioxide is absorbed by the ocean, and when it mixes with seawater it reduces the availability of carbonate ions, scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution said. Those ions are critical for marine life such as shellfish, coral and plankton to grow their shells.

The changing ocean chemistry can have “potentially devastating ramifications for all ocean life,” including key commercial species, according to NOAA.

The New England states are following a model set by Maine, which commissioned a panel to spend months studying scientific research about ocean acidification and its potential impacts on coastal industries. Legislators in Rhode Island and Massachusetts are working on bills to create similar panels. A similar bill was shot down in committee in the New Hampshire legislature but will likely be back in 2016, said Rep. David Borden, who sponsored the bill.

Read more here

Study Committee Calls for Maine to Act on Ocean Acidification

Portland Press Herald, Dec 2nd, 2014 By Kevin Miller

A report to legislators says more research and local efforts are needed to deal with the threat to shellfish, including lobsters and clams.

AUGUSTA — Maine should increase research and monitoring into how rising acidity levels in oceans could harm the state’s valuable commercial fisheries while taking additional steps to reduce local pollution that can affect water chemistry.

Those are two major recommendations of a state commission charged with assessing the potential effects of ocean acidification on lobster, clams and other shellfish. The Legislature created the commission this year in response to concerns that, as atmospheric carbon dioxide levels have risen, the oceans have become 30 percent more acidic because oceans absorb the gas.

Researchers are concerned that organisms that form shells – everything from Maine’s iconic lobster to shrimp and the tiny plankton that are key links in the food chain – could find it more difficult to produce calcium carbonate for shells in more acidic seawater. They worry that the acidification could intensify as carbon levels rise and the climate warms.

Although research on Maine-specific species is limited, the commission of scientists, fishermen, lawmakers and LePage administration officials said the findings are “already compelling” enough to warrant action at the state and local level.

“While scientific research on the effects of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and individual organisms is still in its infancy, Maine’s coastal communities need not wait for a global solution to address a locally exacerbated problem that is compromising their marine environment,” according to an unofficial version of the report unanimously endorsed by commission members Monday.

The panel’s report will be presented to the Legislature after Monday’s final edits are incorporated. Those recommendations include:

• Work with the federal government, fishermen, environmental groups and trained citizens to actively monitor acidity changes in the water or sediments, and organisms’ response to those changes.

• Conduct more research across various species and age groups to get a better sense of how acidification is affecting the ecosystem.

• Identify ways to further reduce local and regional emissions of carbon dioxide – a greenhouse gas produced by the combustion of fossil fuels – and to reduce runoff of nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients that can contribute to acidification.

• Reduce the impact of acidification through natural methods, such as increasing the amount of photosynthesizing marine vegetation like eelgrass and kelp, promoting production of filter-feeding shellfish operations, and spreading pulverized shells in mudflats with high acidity.

• Create an ongoing ocean acidification council to monitor the situation, recommend additional steps and educate the public. This recommendation is the only concrete legislative proposal contained within the report.

Read more here

How to Battle Ocean Acidification

June 16th, By John Upton, Pacific Standard (psmag.com)

It’s a fearsome problem. But we’re not just watching helplessly.

Shellfish are dying by the boatload, their tiny homes burned from their flesh by acid. Billions of farmed specimens have already succumbed to the problem, which is caused when carbon dioxide dissolves and reacts with water, producing carbonic acid.

When ocean life starts to resemble battery gizzards, how can humans possibly respond?

Immediately curbing the global fossil fuel appetite and allowing carbon dioxide-drinking forests to regrow would be obvious steps. But they wouldn’t be enough. Oceanic pH levels are already 0.1 lower on average than before the Industrial Revolution, and they will continue to decline as our carbon dioxide pollution lingers—and balloons.

In a recent BioScience paper, researchers from coastal American states summarized what we know about ocean acidification, and described some possible remedies.

As John Kerry kicks off two days of ocean acidification workshops, here’s our summary of the scientists’ overview:

WHAT WE KNOW

- Acid rain can affect ocean pH, but only fleetingly, especially when compared with the effects of carbon dioxide pollution.

- Studies of naturally acidified waters, like those near CO2 vents, suggest that acidification will depress species diversity; algae will continue to take over.

- Farm runoff and fossil fuel pollution can worsen the problem in coastal areas. The nitrogen-rich pollution fertilizes algae. That initially reduces CO2 levels, but the plankton is eaten after it dies by CO2-exhaling bacteria. This type of pollution appears to be worsening the acidification of the Gulf of Mexico.

- Strong upwelling, in which winds churn over the ocean and bring nutrients and dissolved carbon dioxide up from the depths, exacerbate local acidity levels in some regions. In the upwell-affected Pacific Northwest, climate change appears to be leading to stronger upwelling.

- Shellfish are “highly vulnerable” to ocean acidification. Some marine plants may benefit. Fish could suffer from neurological changes that affect their behavior. Coral reefs are also being damaged.

- Declining mollusk farm production could cost the world more than $100 billion by 2100.

- Marine plants can help buffer rising acidity. Floridian seagrass meadows appear to be protecting nearby coral.

WHAT’S BEING DONE

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration created an ocean acidification program in 2012. It’s monitoring impacts, coordinating education programs, and developing adaptation strategies.

- American experts are talking less these days about ocean acidification as a universal problem, and becoming more focused on local and regional solutions.

- Alaska, Maine, Washington, California, and Oregon have initiated studies and working groups.

WHAT MORE COULD BE DONE

- The EPA could enforce the Clean Water Act to protect waterways from pollution that causes acidification.

- Other coastal states could model new working groups on the Washington State Blue Ribbon Panel, which helped form the West Coast Ocean Acidification and Hypoxia Science Panel.

- Incorporate ocean acidification threats into states’ coastal zone management plans.

- Expand the network of monitors that measure acidity levels, providing researchers and shellfish farmers with real-time and long-term pH data.

- Expand marine protections to reduce overfishing and improve biodiversity, which can allow wildlife to evolve natural defenses.

Source: http://www.psmag.com/navigation/nature-and-technology/how-battle-ocean-acidification-83489/

One of the Smartest Investments We Can Make

Ensia.com. By Jane Lubchenco and Mark Tercek, April 14th, 2014

For centuries, coastal wetlands were considered worthless. It’s time to acknowledge the environmental and economic value of restoring these ecosystems.

For the past 25 years, every U.S. president beginning with George H. W. Bush has upheld a straightforward, three-word policy for protecting the nation’s sensitive and valuable wetlands: No Net Loss. And for a quarter of a century, we have failed in this country to achieve even that simple goal along our coasts.

According to a recent report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the United States is losing coastal wetlands at the staggering rate of 80,000 acres per year. That means on average the equivalent of seven American football fields of these ecosystems disappear into the ocean every hour of every day. On top of that, we’re also losing vast expanses of sea-grass beds, oyster reefs and other coastal habitats that lie below the surface of coastal bays.

Rising sea levels make coastal wetlands increasingly important as a buffer from erosion. Under the right circumstances, wetlands are even capable of building up coastal lands.

This isn’t just an environmental tragedy; it’s also an economic one. Coastal wetlands and other coastal habitats provide buffers against storm surges, filter pollution, sequester carbon that would otherwise contribute to climate change, and serve as nurseries to help replenish depleted fish, crab and shrimp populations. The result is reduced flooding, healthier waterways, and increased fishing and recreational opportunities. To reap these benefits, we must reverse the trend of coastal habitat loss and degradation by protecting remaining habitats and aggressively investing in coastal restoration.

The good news is that such investments can pay off handsomely. To determine the extent of the economic contributions of these fragile and fading ecosystems, the Center for American Progress and Oxfam America analyzed three of the 50 coastal restoration projects NOAA carried out with funding from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The results were very positive. All three sites — in San Francisco Bay; Mobile Bay, Ala.; and the Seaside Bays of Virginia’s Atlantic coast — showed strong average returns on the dollars invested.

Only part of this benefit came from construction jobs. Real, long-term benefits also accrued to coastal residents and industries in the form of increased property values and recreational opportunities, healthier fisheries, and better protection against inundation. Rising sea levels make coastal wetlands increasingly important as a buffer from erosion. Under the right circumstances, wetlands are even capable of building up coastal lands because they trap sediment coming downstream from rivers, creating new land where additional marsh vegetation can grow.

Nervous Nemo: Ocean Acidification Could Make Fish Anxious

By Douglas Maine, December 6th, 2013 Livescience.com

Ocean acidification threatens to make fish, like this juvenile rockfish, more anxious.

Credit: Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Ocean acidification, which is caused by rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere being absorbed into the sea, has made many worry because of the problems it will likely create, such as a decline in shellfish and coral reefs. But humans may not be alone in their anxiety: Ocean acidification threatens to make fish more anxious as well (and not because they are reading about ocean acidification on LiveScience.com. At least so far as we know.)

A new study found that after being placed for a week in an aquarium with acidic seawater — as acidic as the oceans are expected to be on average in a century’s time — juvenile rockfish spent more time in a darkened corner, a hallmark of fish anxiety, and the same behavior exhibited by fish given an anxiety-inducing drug.

“They behaved the same way as fish made anxious with a chemical,” said Martin Tresguerres, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego.

Coastal states respond to ocean acidification

December 16th, 2013

Ocean acidification is warming up policy discussions about marine resources.In fact, state agencies and legislatures in the Pacific Northwest and Northeast are considering new laws and regulations to mitigate the effects of climate change on shellfish harvesters and other marine industries.

In August, California and Oregon established the West Coast Ocean Acidification and Hypoxia Science Panel.This panel was tasked with developing new research and policy proposals to respond to risks from ocean acidification.Those states’ action built on a November 2012 report by the Washington State Blue Ribbon Commission on Ocean Acidification (Commission) that resulted in the creation of a new state panel in Washington to analyze policies to mitigate ocean acidification.1

On the East Coast, Maine’s State Legislature passed a joint resolution in March recognizing ocean acidification as a direct threat to Maine’s economy, particularly to clams, mussels, and lobsters. It called for “research and monitoring in order to better understand ocean acidification in the Gulf of Maine and Maine’s coastal waters, to anticipate its potential impacts on Maine’s residents, businesses, communities and marine environment and to develop ways of mitigating and adapting.” 2 A bill to fund further study of ocean acidification was submitted to the legislature in October, although it now appears this bill will be postponed until Maine’s January session.

TILLAMOOK, Ore. – The Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery is quietly tucked away off the Netarts Bay in Tillamook.

TILLAMOOK, Ore. – The Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery is quietly tucked away off the Netarts Bay in Tillamook.